Privacy is not dead, as the results of a major telephone survey of more than 27,000 respondents across Europe has found: 87% felt that protecting their privacy was important or very important to them. Even more, 92%, said that defending civil liberties and human rights was also important or very important.

The survey may be the most detailed assessment of how people in 27 EU Member States feel about privacy and security. It was conducted as part of the EU-funded PRISMS project (not to be confused with the once-clandestine PRISM program under which the US National Security Agency was collecting Internet communications of foreign nationals from Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Yahoo and other US Internet companies).

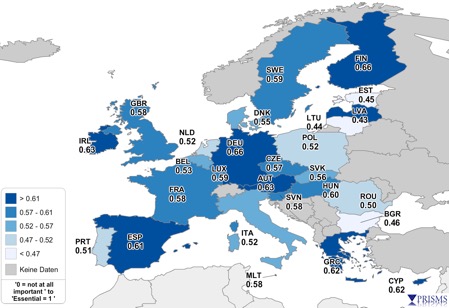

The survey showed that privacy and security both are important to people. There were some consistent themes, e.g., Italy, Malta and Romania tend to be more in favour of security actions, while Germany, Austria, Finland and Greece were less so. Respondents were generally more accepting of security situations involving the police than the NSA.

60% said governments should not monitor the communications of people living in other countries, while one in four (26%) said governments should monitor such communications, while the remainder had no preference or didn’t know. Predictably, there were significant differences between countries. Three out of four respondents in Austria, Germany and Greece said governments should not monitor people’s communications, which was somewhat higher than most other EU countries.

70% of respondents said they did not like receiving tailored adverts and offers based on their previous online behaviour. 91% said their consent should be required before information about their online behaviour is disclosed to other companies. 78% said they should be able to do what they want on the Internet without companies monitoring their online behaviour. 68% were worried that companies are regularly watching what they do.

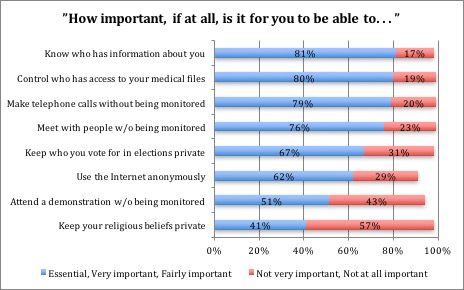

Some other results: 79% of respondents said it was important or essential that they be able to make telephone calls without being monitored. 76% said it was important or essential that they be able to meet people without being monitored. More than half (51%) felt they should be able to attend a demonstration without being monitored.

80% said camera surveillance had a positive impact on people’s security; 10 % felt it made no difference and even fewer (9%) felt it had a negative impact. Almost three-quarters (73%) said the use of body scanners in airports had a positive impact on security, while fewer than one in five (19%) felt that the use of scanners had a negative impact on privacy. 38% said smart meters threatened people’s rights and freedoms.

More than one in five (23%) said they had felt “uncomfortable” because they felt their privacy was invaded when they were online. Almost the same (21%) felt uncomfortable because they felt their privacy was invaded when a picture of them was posted online without their knowing it. By contrast, a substantial majority (65%) didn’t feel uncomfortable when they were stopped for a security check at an airport. Respondents were asked if they had ever refused to give information because they thought it was not needed. 67% said yes, while 31% said no. Half of all respondents said they had asked a company not to disclose data about them to other companies.

While the survey generally showed that people were concerned about their privacy, there were some surprises. For example, 57% said it was not important to keep private their religious beliefs. Almost one-third (31%) said it was not important to keep private who they vote for. Only 13% had ever asked to see what personal information an organisation had about them. More than half (51%) had not read websites’ privacy policies.

Respondents had a very nuanced view of surveillance and its impact on their privacy. Support or opposition to surveillance depends on the technology and the circumstances in which it is employed, if for example the surveillance activity was targeted and independently overseen.

The interviewers gave respondents eight vignettes, or mini-scenarios, and then asked them for their views on the privacy and security impacts, some of which are highlighted below. The vignettes concerned crowd surveillance at football matches, automated number plate recognition (ANPR), monitoring the Internet, crowd surveillance, DNA databases, biometric access control systems, NSA surveillance and Internet service providers’ collection of personal data.

A sizeable minority (30%) felt that monitoring demonstrations threatened people’s rights and freedoms, but that figure fell to 19% if the monitoring was of football matches. 70% felt crowds at football matches should be surveilled; 61% said surveillance at football matches helped to protect people’s rights and freedoms.

Opinion was more evenly divided about DNA databases: 47% felt that DNA databases were okay compared to 43% who did not agree. However, a substantial majority, 60%, opposed NSA surveillance and 57% felt NSA surveillance threatened people’s rights and freedoms.

Also predictably, there were differences in political views. 68% of people on the left felt that foreign governments’ monitoring people’s communications was a threat to their rights and freedoms, compared to 53% of people on the right who felt this way. 60% said these practices made them feel vulnerable. More than half (53%) did not feel these practices made the world a safer place. 70% did not trust government monitoring of the Internet and digital communications. In response to a question about how much trust they had on a scale of 0 (none) to 10 (complete) in various institutions, more than half (51%) of all respondents said they had little or no trust in their country’s government compared to 39% in the press and broadcasting media and 31% in the legal system. Half of all respondents had some or complete trust in businesses, and an astounding 70% trusted the police.

Interviewers described a scenario in which parents find out that their son is doing some research on extremism and visits online forums containing terrorist propaganda. They ask him to stop because they are afraid that the police or counter-terrorism agencies will start to watch him. 68% said security agencies should be watching this kind of Internet use, compared to 20% who said they should not. 53% said security agencies’ doing this helps to protect people’s rights and freedoms. One in five (22%) disagreed. 41% of respondents felt that parents should worry if they find their child visiting such websites. One in five felt parents should not worry because they believed that security agencies can tell the difference between innocent users and those they need to watch.

Another vignette concerned companies wanting to sell information about their customers’ Internet use to advertisers. The companies say the information they sell will be anonymous, but 82% of respondents still said service providers should not be able to sell information about their customers in this way. The figure was 90% in Germany and France, the highest in Europe. 72% of respondents in the UK and across the Union felt such practices were a threat to their rights and freedoms.

The European PRISMS project started in February 2012 and finished in August 2015. The project has been analysing the traditional trade-off model between privacy and security and devising a more evidence-based perspective for reconciling privacy and security. Among other things, the project is examining how technologies aimed at enhancing security are subjecting citizens to an increasing amount of surveillance and, in many cases, causing infringements of privacy and fundamental rights. The project is also devising a decision support system aimed at those who deploy and operate security systems so that they take better account of how Europeans view privacy and security.

The project has been undertaken by a consortium comprising eight partners from five countries: the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research (Germany), TNO, the Dutch research organisation, Zuyd University (Netherlands), the Free University of Brussels, the Eötvös Károly Policy Institute (EKINT) in Hungary and three partners from the UK: Trilateral Research, Ipsos MORI and Edinburgh University.

Ipsos MORI conducted the interviews between February and June last year, since when the other partners have been poring over the results and are now making some of the survey results and their analysis publicly available. The PRISMS consortium said further analysis of the survey data would examine the relationships between demographics, attitudes and values in relation to privacy and security.

More results from the PRISMS project can be found at prisms-project.eu.

David Wright and David Barnard-Wills